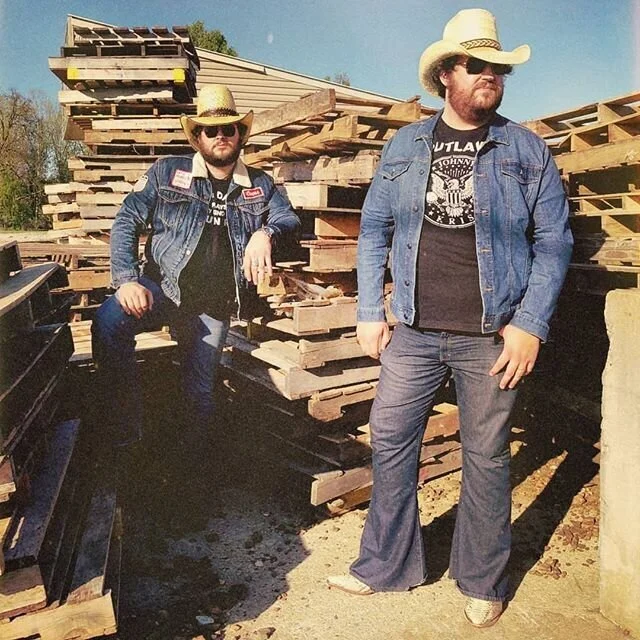

The Reeves Brothers: The Last Honky-Tonk

Some music just isn’t meant to sit still. Or to be listened to sitting still for that matter. It blows and goes, eats and runs, and leaves the bottles in your cabinet a little lighter. A ratty note bidding ‘thanks and hasta luego’ on your kitchen counter-top with exhaust smoke lingering in your driveway and 18 wheels down the road.

A feeling of nostalgia and transience is what washed over me when I popped my headphones in and pressed play on The Reeves Brothers latest full-length endeavor, The Last Honky-Tonk, a fitting title and tone for the times we find ourselves passing through.

Shades of Waylon, Johnny Paycheck, and Merle cover the country side of things with tinges of Willie Nelson and Johnny Rodriguez on the more western numbers like the title track. A clear resonation comes across in the recordings that these are students of the genre. This isn’t simply a posse that has made a trip to the local Western Wear store and done some casual Google-ing to figure out how to outwardly appear to be country. This is the reflection of individuals who have saturated their internal cogs with the roadhouse lifestyle. Some might make comparisons to masterful contemporary country acts like Mike & The Moonpies, but The Reeves Brothers journey has run parallel and delivers their own version of truth and reality. Speaking frankly, the only similarity I could find is they, alongside bands like The Moonpies, are part of only a literal handful of Country & Western bands that are tastefully keeping old traditions alive while simultaneously evolving; a feat only achieved by a steadily dying breed in the modern music world - the real thing.

The Kevin Skrla (The Broken Spokes) produced record begins in high gear with “100 Proof Honky-Tonk” - a smoking shuffle with shades of The Killer pounding the life out of the keys on a chimey barroom piano. Simple, yet clever turns of phrase such as “don’t serve it on the rocks because I’ve lived there way too long” and “I’m still crazy, but you’re out of my mind” in a later track display lyrical aptitude. An understanding, as is in all the great Country Canon, that less was always more.

We then transition into a ballad that chronicles the tale of a reminiscing truck driver looking to the rear-view to recall a truck stop beauty who once hitched a ride down the road with him by the name of Gypsy-Rose. This number, “The Ballad of Alabama Gypsy-Rose,” sets the precedent that this isn’t simply going to be a record bound to the bottle. The following track, “Tucson,” paints a similar picture of yet another weary traveler who found comfort somewhere along his journey on the highways and byways of America, padded with beautiful rollicking rhythm and sustaining strings. The journey isn’t always fresh blacktop and trafficless commutes, but in this instance, comfort was found by way of Tucson. Traveling right along, the protagonist in “Little Rock” moves eastward while understanding that maybe he’s not the only one in motion as he watches his true love disappear into the horizon. A common thread throughout the record is the personification of women as towns, or giving human characteristics and feelings to inanimate objects (such as a bottle of hooch), a lyrical device commonly employed and somewhat pioneered by greats such as Kristofferson.

“I’m Still Crazy” kicks with a Skrla pedal steel intro (executed by Caleb Melo) which is the glue that cascades over and coats the sonic landscape of the record like a shining paint job on a freshly-washed Peterbilt. Finally we meet a character that rather than subsiding to self-pity, they’re taking matters into their own hands and scrubbing their troubles away down the drain. Though it’s Budweiser that acts as the medicine in this particular instance, later in the record we crack back into the harder stuff. Perhaps due to sadness, or perhaps from the hangover brought on by the previous track, the Brothers proclaim “they’ve lost all the strength to sing the blues.” This track, “I've Lost All My Strength to Sing the Blues,” is relatable on so many levels, as so many of us are now graced with a surplus of time, yet the grey that saps the blue from our soul sucks the creative spirit dry as we sputter to a stop on the shoulder.

The title track (and also the standout track), “The Last Honky-Tonk” laments the fact that keeps people who have rural America at their core awake in the dead of the night. The fact that what makes us “us” is dwindling down to the slim pickings and urban sprawl, and technological automation is suffocating the crops in the fields and the hands that build. Lyrically, it is concise and potent. A clear play on “Mamas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to be Cowboys'' in a way that pays homage and comes clean with no fluff in regards to the matter at hand, that we are losing our wide open spaces and honest places. After a punch in the gut, the record mounts back up and digs the spurs in with “It Gets Cold at Night in California.” Perhaps a lover from songs past, or perhaps yet another love gone wrong, the track drives along with twinning guitar parts and crisp hi-hats with classic Haggard vibes.

With “No. 7 Blues,” a clear nod to one of the pioneers of Country music, Jimmie Rodgers, we hear a more contemporary and straightforward lyrical approach with a character who’s dabbled in too much of the brown stuff (of the Tennessee-sipping variety). The slippery slope doesn’t stop there, as “My Good Friend and Buddy,” does the protagonist wrong yet again. A barroom rouser that would give Gamble Rogers a run for his money in sheer knowledge and intimacy with ol’ Jack Daniels, a belligerent antagonist who “drug them to the gutter to die.”

Songs like the next track, “Stagestop Bar,” can only be written from experience; marinating in the thick smoke and stale liquor musk of a roadhouse. This is a real joint that the Reeves Brothers themselves, who grew up in Nevada, with their father being a member of the house band at the bar of that same name. It is written from an honest angle, so much so that a song like this is as close you can get to those places without actually being bellied up to the bar or cutting through the saw dust on the hardwood floor.

We are finally bid “Farewell” with the 12th and final track. Jealousy reigns supreme as we watch an old flame fall back in love with a new lover. We are left in perpetuity with a broken heart yet simultaneously lifted spirits in regards to the state of the genre at the conclusion.

Arrangements that trade off with intent and smoothness, tempo changes and dynamic shifts that unfurl with no kinks, and a steady and true vocal delivery. This is one of the best pure Country & Western records I have heard in perhaps a decade. Though at times the subject matter and lyrical cadence can feel slightly redundant and safe, upon a second & third listen you understand like so many great records, that it is designed that way. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, and this rig that The Reeves Brothers have tuned up is running & humming along with finesse. And it’s just about to merge onto the Interstate. I look forward to seeing where it’s heading. Highly recommend this one for fans of the real deal.

Find more about The Reeves Brothers here: